Radical markets

In the short run, the market is a voting machine but in the long run, it is a weighing machine.

- Benjamin Graham

Radical markets is a technique that illuminates complex problems by parameterizing nearly anything in the world by price (e.g. bananas, scientific progress, time, human life), and letting market participants find the equilibrium between buyers and sellers. One way to think of this technique is as applied microeconomics. Prices carry information about people’s beliefs, and are difficult to consistently falsify; so radical markets is a means of solving problems by capturing aggregate information.

Illustrative example

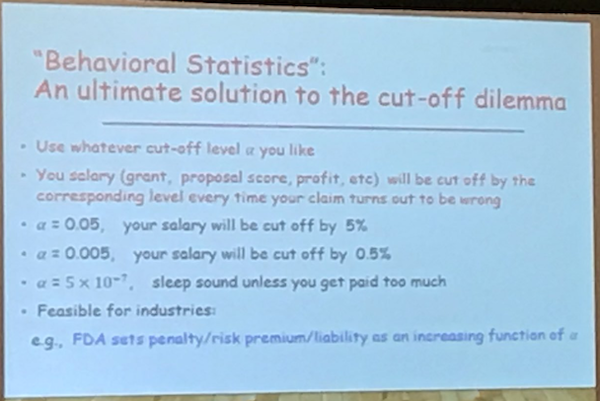

My favorite example of radical markets comes from a Harvard statistician Xiao-Li Meng (h/t David Robinson). Meng proposed a market solution to the following problem: which p-value cutoff should scientists use for hypothesis testing? If the cutoff is too low, science will progress slower than it needs to because the standard of evidence is unnecessarily high. If the cutoff is too high, we may find ourselves in a replication crisis. This problem is further exacerbated by p-hacking– scientists are incentivized to understate the risk of false positives.

Meng proposed the following approach– you can use whatever cutoff you want, but your salary will be cut by the corresponding level every time your claim turns out to be wrong.

Your first reaction might be “this will never work!”, but the more you think about this proposal, the more its benefits become apparent. It eliminates p-hacking incentives, discourages publishing results that scientists know ex ante are unlikely to be replicated, broadly aligns incentives of individual scientists with aggregate scientific progress, and eliminates the need for magic constants. Scientists who are convinced in their results but don’t have sufficient evidence can credibly signal their confidence to the scientific community by picking a high cutoff.

More examples

Here is an example of a similar problem in a completely different domain: how should the government assess the value of property for the purpose of taxation? Via Should we move to self-assessed property taxation:

The core proposal is you announce how much each piece of your property is worth, and you are then taxed as a percentage of that value (say 2.5%). At the same time, you have to sell your property for that same value, if someone bids for it, thereby lowering or eliminating the incentive to under-report true values. If you think this through, you can see it minimizes holdout problems.

More on this at Between Property and Liability:

This would avoid administrative property valuations, discourage people from sitting on stuff they don’t use, and make it much easier to assemble property into large units. Eminent domain would no longer be needed.

(The authors of the proposal Eric Posner and Glen Weyl have a book– Radical Markets– with even more examples of this technique).

܍

Note that you don’t necessarily need to set up a market– you can use this technique to run a thought experiment. (This isn’t as good of course, as there is a huge difference between actually choosing to pay vs hypothesizing, but running the thought experiment still gives you a lot of information.) As an example, in radical quantification we dealt with a question: how much richer is an average American in 1992 than an average American in 1800? There I quoted from William Nordhaus’s approach to measure the number of hours necessary to work to produce a lux of light.

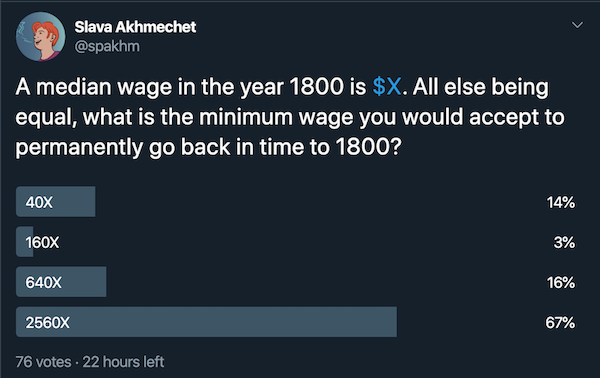

Another approach would be to pay people to move to 1800, and use the price buyers are willing to accept as information. There is no time machine, so we can’t run the experiment. But we can run a thought experiment. Here is an example I tried on Twitter:

The methodology here is really simple, but it does give us some information– most people who chose to participate in the poll seem to value the technological advancements between 1800 and now at a very high multiple.

܍

A more general example of this is the idea of prediction markets. The conceit is that on average a betting market will give you a better prediction of the future (and therefore a better mechanism to make decisions) than mechanisms in existing use:

Prediction markets continue to offer great potential to improve society at many levels. Their greatest promise lies in helping organizations to better aggregate info to enable better key decisions. […] such markets have consistently performed well in terms of cost, accuracy, ease of use, and user satisfaction […]

Robin Hanson also proposed Futarchy– a hypothetical system of government based on prediction markets:

In futarchy, democracy would continue to say what we want, but betting markets would now say how to get it. That is, elected representatives would formally define and manage an after-the-fact measurement of national welfare, while market speculators would say which policies they expect to raise national welfare. The basic rule of government would be: When a betting market clearly estimates that a proposed policy would increase expected national welfare, that proposal becomes law.

܍

Another wonderful example of radical markets is by the Harvard anthropologist Joseph Henrich: Does Culture Matter in Economic Behavior? Ultimatum Game Bargaining Among the Machiguenga of the Peruvian Amazon. Henrich uses the ultimatum game to explore (and quantify) the concept of fairness and obligation across different cultures:

One player, the proposer, is endowed with a sum of money. The proposer is tasked with splitting it with another player, the responder. Once the proposer communicates their decision, the responder may accept it or reject it. If the responder accepts, the money is split per the proposal; if the responder rejects, both players receive nothing. Both players know in advance the consequences of the responder accepting or rejecting the offer.

The paper is worth reading in full, but here is a salient quote (edited for context):

Roth, in examining the difference found between American and Israeli proposers, suggests that the results indicate a difference in what is perceived as “fair,” or what is “expected” under the circumstances. My comparison of Machiguenga and Los Angeles subjects yields a similar conclusion, only more extreme. Machiguenga proposers seem to possess little or no sense of obligation to provide an equal share to responders, and responders had little or no expectation of receiving an equal share nor any desire to punish unequal divisions. The modal offer of 15 percent seemed quite “fair” to most Machiguenga.

This post is part of the Creative Library– a series of clever techniques that simplify solving complex problems.